A Waymo Visit Brings Way More Future Mobility Insight

I did a little recon work prior to my visit this week to Google’s autonomous vehicle division, Waymo.

I wanted to get a sense of how driverless vehicle technologies might be underway and visible in California’s high-tech corridors.

Jay Seirmarco, an assistant general counsel for Cox Automotive who lives in San Francisco and works at Xtime’s offices in Redwood City, relayed that driverless vehicles are already common during typical commute times in his Noe Valley neighborhood.

“There are numerous autonomous vehicles coming into my neighborhood every morning,” he says. “The rumor mill  in the neighborhood is that Apple workers are taking some of these to work. This happened recently and the volume is amazing. For me, it’s been an epiphany—this is the real deal and some people are commuting in these things.”

in the neighborhood is that Apple workers are taking some of these to work. This happened recently and the volume is amazing. For me, it’s been an epiphany—this is the real deal and some people are commuting in these things.”

Lucy Smith, a Cox Automotive corporate counsel who lives in Redwood City, affirms that driverless vehicles are common during her daily commute. It’s also pretty common to see Teslas with drivers whose hands aren’t on the steering wheel.

“These vehicles are fantastic at handling traffic,” she says. “They actually drive better than some human drivers. They change lanes much more expertly.”

Those on-the-ground observations helped inform my meeting with Waymo CEO John Krafcik and COO Shaun Stewart. I had a rough sense that driverless vehicle adoption and use was gaining ground, and a hunch that it might be more profound than what I’ve read in industry and mainstream press.

The following are some of the big take-aways from my meeting with the Waymo executives and a drive in one of their vehicles—what I’ve come to call “My Trip to the Mountain”:

The technology is intense. Our vehicle arrived precisely at 9:30 a.m., exactly when it was supposed to. The vehicle, a Chrysler Pacifica, had two engineers in the front seat with laptops. They weren’t driving the vehicle as much as monitoring its performance and answering our questions. Between them, the dashboard featured a monitor showing a grid with images of color-coded objects ahead—other vehicles, street lights/signs, pedestrians, cyclists, etc.

The image colors changed to denote whether a specific vehicle sensor, a camera or laser radar, captured the object. The colors also changed based on movement and proximity to our vehicle.

At one point during the ride, a cyclist rode up beside our vehicle and passed us. I asked the engineers how the vehicle knew it was a cyclist and where he was going. “We calculate the probability of what the cyclist will do,” I was told. I asked the obvious follow-up—“how do you do that?”

The explanation was pretty incredible. The sensors track the cyclist’s position on the road, the angle of the rider/bike frame, and other factors to predict where it’s headed.

My mind spun as I thought about all of the data-crunching and programming necessary to produce such predictions.

Seirmarco shared a similar experience: He recently watched a driverless vehicle at a four-way intersection assess a cyclist, who was rolling backwards and forwards for balance while waiting for a vehicle to pass. The autonomous car appeared to stop and start in sync with the cyclist, and then proceed.

“The car figured it out,” Seirmarco says. “It blew my mind that the car knew what to do.”

Driverless vehicle critical mass will take about 10 years. Krafcik and Stewart helped me understand that some predictions, like one that says 100 percent of vehicles will have Level 5 autonomous technology by 2021, are a bit far-fetched. They also thought other predictions, like one that views 2030 as the point when autonomous vehicles will achieve critical mass, as about right. I came away thinking “10 years” is probably a viable timeframe when driverless vehicles will show up more commonly in places outside of California’s tech-heavy communities.

“Taxi” will mean something different to all of us. We discussed Waymo’s plans to commercialize its driverless vehicles with a “taxi” offering in Phoenix. The conversation helped me better understand Waymo’s intentions to operate fleets of autonomous vehicles, and offer them in a model that enables one vehicle to serve many different customers, sometimes at the same time. We didn’t dig into how consumers might pay for this type of transportation. But it’s likely the model will blend pay-per-use or pay-per-term principles. It seems like the idea of “calling a cab” may mean something entirely different in the not-too-distant future, and the Phoenix experiment bears watching.

in a model that enables one vehicle to serve many different customers, sometimes at the same time. We didn’t dig into how consumers might pay for this type of transportation. But it’s likely the model will blend pay-per-use or pay-per-term principles. It seems like the idea of “calling a cab” may mean something entirely different in the not-too-distant future, and the Phoenix experiment bears watching.

OEMs will compete and partner with Waymo. We spent some time discussing the seeming arms race among OEMs around driverless vehicle technology. The dialogue helped me understand that Waymo and others will probably go head-to-head with larger OEMs, and partner with smaller OEMs that may find it difficult to develop driverless technologies on their own. The partnerships might take several forms, ranging from efforts to integrate the sensors and related technologies into vehicle designs and supply the vehicles Waymo and others will need.

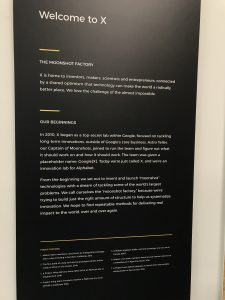

Waymo shares our values. Both executives impressed me with their keen, shared sense of personal and social responsibility. They care about their people and their broader communities—just as we do at Cox Automotive. I also liked the way the company’s committed to innovation. Their mission talks about making “moonshots” (see image) and we are focused on “transforming the way the world buys, sells and owns cars.”

I would be remiss to not share how the discussion of shared purpose and values offered a positive outlook for Cox Automotive. The executives were sincere in saying they believed Cox Automotive would play an important role in the future of mobility and Waymo’s efforts to shape it.

I left the meeting thinking: “They know us. They understand what we do. They get why we do it. This is good.”