Understanding The New Math of Today’s Used Car Business

There was a time not long ago when selling used vehicles and making money were synonymous.

Those were the days when you could take a used vehicle into inventory, price it to achieve your gross profit objective and reasonably expect to make your money, or at least a decent portion of it, even if it took 60 days or more to find a retail buyer.

That’s why, if you asked dealers and used vehicle managers whether they were in the business of selling cars or making money, most would answer, “Selling cars”—since that’s all it really took to make money.

But I’d argue that we’re in a different era today, and that the dealer-favorable conditions that assured we might retail a used vehicle and make money have significantly deteriorated. In short, the time has arrived for dealers to focus on making money, not just selling cars.

Consider, for example, how quickly used vehicles run out of margin today compared to just two years ago.

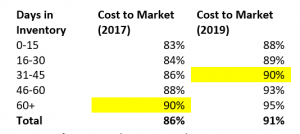

The table at right shows a breakdown of Cost to Market ratios for dealer inventories between 2017 and 2019.

You can see that, in 2017, used vehicles hit a 90 percent Cost to Market ratio around day 60. You could sell the vehicle then, and still make some money even if it wasn’t all you wanted.

But hang on. This year, we’re seeing vehicles consistently hit the 90 percent Cost to Market ratio around day 30!

To make matters worse, if dealers retail vehicles after the 30-day mark today, chances are better than good that the sale won’t generate a net profit contribution.

How can that be, you might ask? Well, consider that the average used vehicle retails at a Price to Market ratio of 93 percent.

If a vehicle has a 90 percent Cost to Market ratio, and sells at a 93 percent Price to Market ratio, you’re left with a 3 percent gross profit. On a $20,000 car, that’s $600.

Now, let’s go a step further, and subtract sales commissions and your department’s expense allocation. I think we can all agree that the $600 disappears pretty quickly and, in most cases, you’re looking at a net loss on the vehicle.

You might call these dynamics the dark underbelly of today’s used car business. They are the reason many dealers finished 2018 scratching their heads: “How is it possible that we sold a record number of used cars and actually lost money?”

My response to these dealers is that they must embrace what I call the “new math of today’s used car business.”

This embrace begins with earnest efforts to balance the new math equation at your dealership, which should be guided by three principles:

First, dealers should maintain inventory levels at no more than a 30-day rolling total of their retail sales. If your rolling 30-day total is 75 vehicles, you should stock 75 vehicles. This benchmark effectively forces acquisition and pricing discipline that’s necessary to retail a larger share of vehicles before they hit the 30-day mark in your inventory. It also dramatically reduces the drag on your operational performance and profitability that owes to retailing older-age vehicles.

Second, dealers need to monitor their performance against the benchmark every day. It’s probably OK if, on any given day or the next, your inventory exceeds the 30-day rolling total of retail sales by a handful of units or less—provided you’re aware of the imbalance and you’re working to fix it.

But if the imbalance grows to 10 or more cars, you can pretty much guarantee you’re setting up sales that won’t produce a meaningful net profit contribution, and probably amount to net losses.

Third, when inventory levels are out of whack against the 30-day rolling total of retail sales benchmark, dealers shouldn’t be out buying cars. Yes, you should take in every trade-in you can that makes sense.

But it doesn’t make sense to buy auction units when you effectively have the cars you need. If you do, the extra vehicles will ultimately throw your inventory further out of balance and make your net losses even worse.

I should add that adopting the new math of the used car business isn’t for the faint-hearted.

It requires discipline, fortitude and will—essentially the same characteristics that anyone who’s in the business of making money would tell you they bring to the job every day.